LLM Evals

How we built open-source automated prompt optimization

contents

Prompt engineering – the process of iteratively writing prompts for LLM systems – is one of the core tasks in LLM system design. However, writing good prompts requires domain expertise, careful wording, and lots of trial and error.

Small changes in prompts can lead to significant swings in LLM outputs’ quality, and it’s often unclear whether a prompt is actually optimal or merely “good enough.” At the same time, like any task that relies on repeated experimentation, prompt engineering itself is a great candidate for automation.

In this blog, we explain:

- What automated prompt optimization is

- Common prompt optimization strategies including search-based, model-internals, self-improvement, and example-based approaches.

- How we designed and implemented automated prompt optimization in the open-source Evidently Python library.

- Available configurations such as early stopping, multiple starts, and different validation metrics.

This blog is based on a webinar “Prompt optimization: from manual engineering to automated improvement using feedback-based optimization”. If you prefer a video, you can watch the recording of the original talk here.

What is automated prompt optimization?

Writing good prompts usually takes a few iterations: you write an instruction, test it, notice what the model gets wrong, tweak the wording, and repeat. The process is fragile and time-consuming.

Many of us already use LLMs to help with this – often by simply prompting them (very meta!) in the chat interface to help expand or rewrite our initial instructions. Often, we then paste back examples of bad outputs and ask the LLM to further improve the prompt. While this works, it’s largely an ad hoc process.

We thought: what if we made it more systematic?

We can treat prompt writing as an optimization loop: automatically generate multiple prompt variants using an LLM, evaluate how well each one performs on a set of examples, and then choose the best one.

As a starting point, this requires two things:

- A test dataset with example inputs

- A way of scoring the quality of outputs you get from your prompt candidates

In many practical cases, it’s actually easier to create an example dataset that shows how a task should be solved instead of writing detailed instructions upfront. For instance, if you have a classification problem, you can create a dataset with example inputs and correct classes, and then ask an LLM to generate a prompt that will successfully perform such classification – it can learn what each label means directly from the data.

This approach resembles classical machine learning model, where you need a labeled dataset to train a model. Except this time, we are creating a natural language prompt instead of tuning model hyperparameters.

You can also use “training” datasets that include additional useful information: for example, beyond correct labels, they can include expert-written natural-language justifications explaining why a particular answer is correct or a specific label is given. The LLM’s task then becomes generalizing the expert’s reasoning into a single, reusable prompt, rather than simply inferring patterns from labels alone.

To evaluate the performance and choose the best prompt in a task like classification, you can use a simple metric like accuracy. More generally, any scoring function that reliably measures the quality of the generated responses can be used. For open-ended tasks, this might involve using an LLM-as-a-judge to evaluate outputs against specific criteria, or implementing another scoring function tailored to the use case.

We decided to experiment with this approach to prompt optimization and implement it in Evidently, an open-source framework for LLM evaluation.

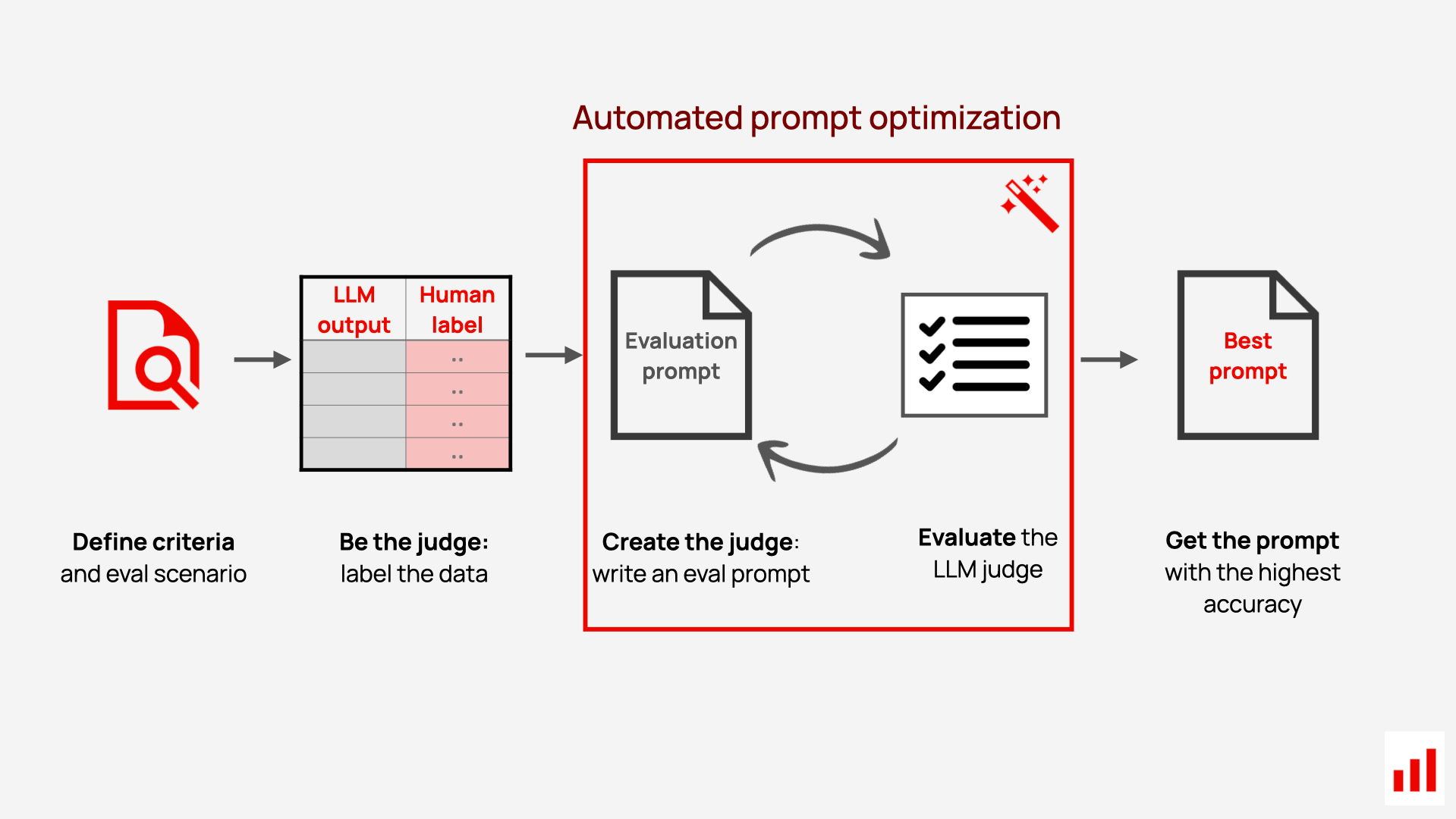

Example task: LLM judge prompt optimization

The first place where we encountered the need for prompt optimization was in generating prompts for the LLM judges – one of the evaluation features in Evidently.

LLM judges help automate LLM evaluations of any custom text property: for example, you can prompt an LLM to classify responses as helpful or not, toxic or safe, actionable or vague, or any other user-defined criterion.

If you want to learn more about LLM judges and how they work, we have a dedicated guide.

An LLM judge is essentially a classifier implemented via a prompt: we ask an LLM to read some text and classify it into two or several classes (e.g., “good” or “bad”).

This is a strong candidate for automated prompt optimization since the evaluation process is quite straightforward: as long as you can construct an example dataset, you can easily measure the judge’s quality through a simple accuracy metric.

Before we dive deeper into how exactly we implemented the automated prompt optimizer in open source, let’s briefly cover other possible approaches to prompt optimization.

Prompt optimization approaches

Before building our own prompt optimization solution, we surveyed the landscape. Broadly speaking, existing methods can be categorized into four main types.

Search-based prompt optimization

Search-based prompt optimization relies on generating a pool of prompt variants, evaluating them, and selecting the best performer. Common techniques include grid search, random search, genetic algorithms, Bayesian optimization, and simulated annealing.

These methods enable systematic exploration and can be effective, but they come with significant drawbacks: they are slow, computationally expensive, and require a large number of LLM evaluations. As a result, brute-force search is rarely practical for prompt optimization at scale.

Model-internals prompt optimization

This class of methods leverages a model’s internal representations – such as gradients, embeddings, and token probabilities – to guide optimization. Examples include gradient-based prompt optimization, continuous prompt optimization, embedding-based methods, differentiable prompt tuning, and soft prompt optimization.

While these approaches can be highly efficient and powerful, they are limited to differentiable models and require full access to model weights and internals. For most teams working with LLMs via APIs (e.g., OpenAI or Anthropic), this makes the approach impractical.

Self-improvement prompt optimization

Self-improvement methods rely on the LLM itself to generate improved versions of a prompt. Examples include manually asking ChatGPT to “improve this prompt,” as well as techniques such as Automatic Prompt Optimization (APO), self-refinement, chain-of-thought optimization, and tree-of-thoughts.

These approaches are attractive because they often work surprisingly well with minimal setup and directly leverage the model’s reasoning capabilities. However, they can become expensive, since LLM calls are required not only to evaluate prompts but also to generate them. They are also highly model-specific: a prompt optimized for one model may perform poorly on others.

Example-based prompt optimization

Example-based optimization – also known as few-shot optimization or demonstration selection – focuses on selecting or refining the examples included in a prompt, rather than modifying the instructions themselves.

This approach can significantly improve performance and is particularly effective in few-shot learning scenarios. However, because it does not directly improve the underlying instructions, it is typically complementary rather than sufficient on its own.

Want to see an example of prompt optimization? Follow this example notebook or watch the recording of a live coding session.

How automated prompt optimization works in Evidently

With our implementation, we aimed for a solution that:

- Works with limited labeled data,

- Produces interpretable results,

- Is practical, configurable, and easy to use,

- Integrates with evaluation workflows in the Evidently library, but can also be used standalone.

We ended up following a hybrid approach, centered on self-improvement but borrowing ideas from search-based and example-based methods.

Prompt optimization workflow

Let’s look at how our solution automates the generation of LLM-judge prompts using expert-labeled data. Here’s how it works from the user standpoint:

- Label examples. The first step requires you to provide a dataset with example labels. Essentially, you need to act as the judge first – label LLM outputs (summaries, replies, reviews, etc.) using binary or multi-class labels and the same grading criteria as you later want the LLM to use. You can do it yourself or with the help of domain experts.

- (Optional) Add expert comments. While you can run the prompt optimization using just labels, you can also expand the dataset to add comments. Short notes, such as “too wordy” or “misses a key detail,” explaining why a specific label was assigned, will help the optimizer learn specific decision patterns.

- Run the prompt optimizer. From there, you can start the optimization using our implemented approach. The optimizer will try generating prompts using the provided dataset as an input and evaluate multiple prompt variants, scoring each by how well the LLM judge matches the human labels.

- Get the result. You receive the best-performing judge prompt ready for use.

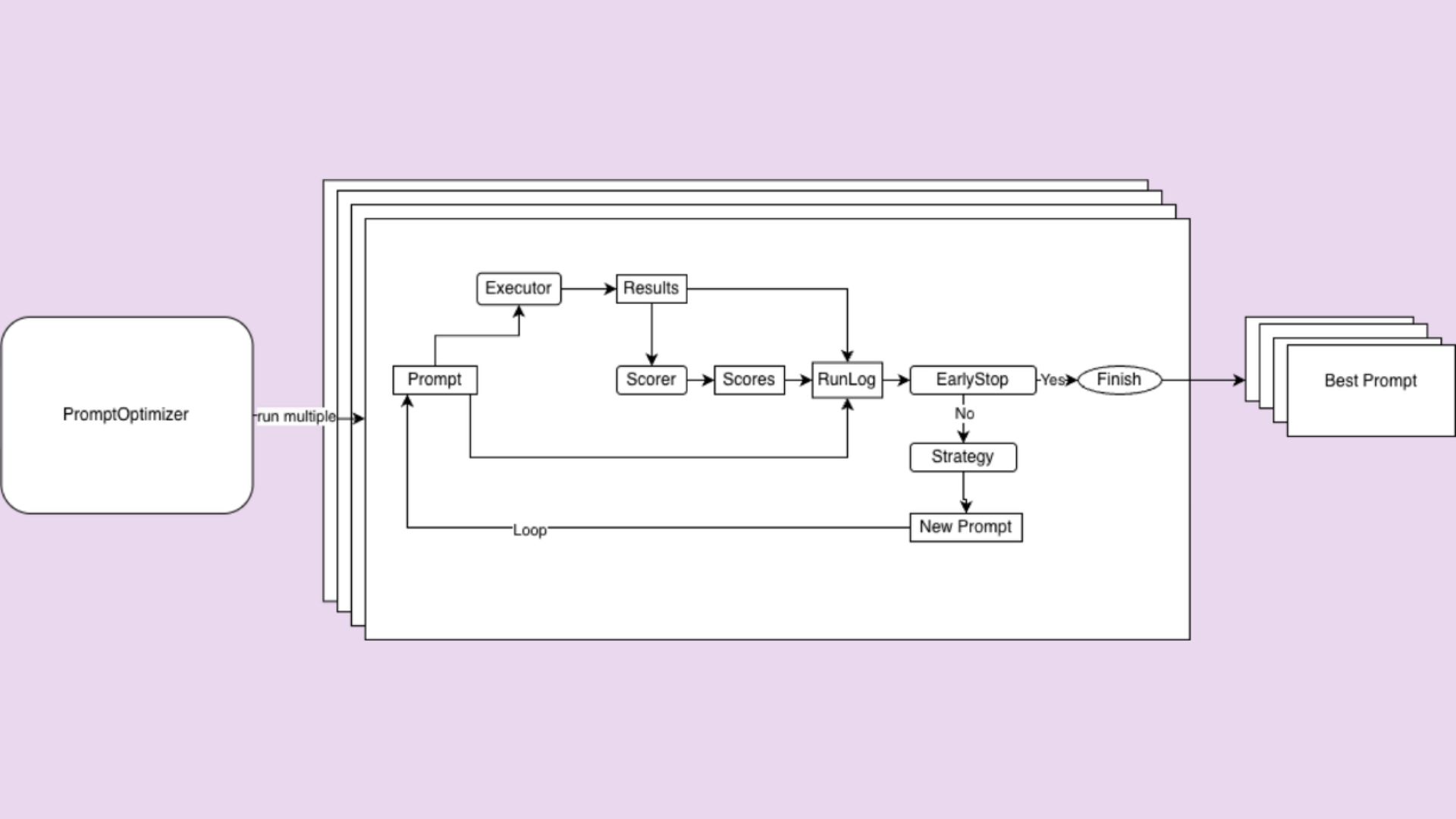

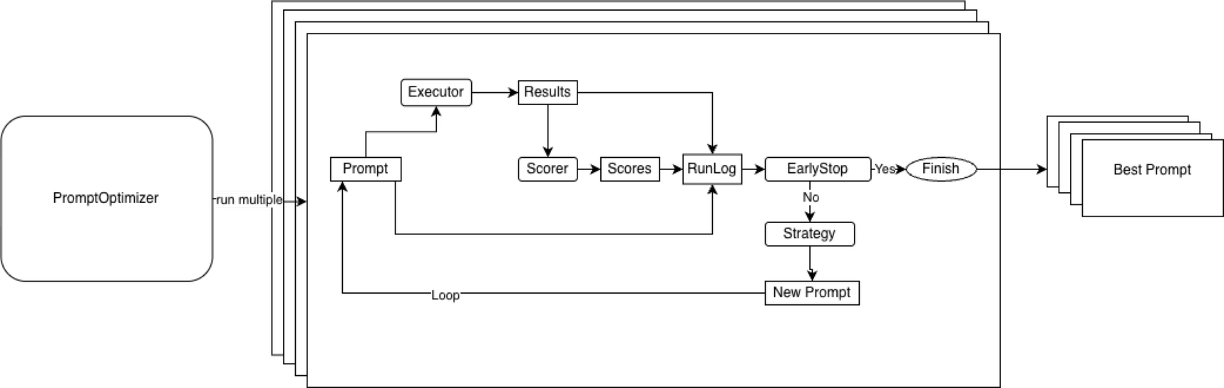

Automated prompt optimizer architecture

Now, let’s take a look at how this works inside. At the core of our implementation is a simple but flexible architecture with three components:

1. Strategy

The strategy determines how to generate the next prompt, taking into account all information seen so far, including previous prompts, scores, and results. The solution has two built-in strategies:

- Simple strategy: asking an LLM to improve the initial prompt

- Feedback strategy, or mistake-driven iterative improvement: asking an LLM to improve the prompt, considering the errors (like classification errors) made at the previous prompt iteration

The component is customizable – you can also create and use your own strategy if you feel like it!

2. Executor

The executor takes a prompt and produces outputs. For LLM judges, this means running the judge over a labeled dataset and producing predicted classes.

3. Scorer

The scorer performs the evaluation of the generated outputs. For example, if you choose the built-in “accuracy” scorer, it will сompare the outputs to ground-truth labels and return the final metric. (Another built-in scorer option lets you use an LLM judge configured with the Evidently library as the evaluator).

Users can plug in custom scorers if needed.

These three pieces are orchestrated by a PromptOptimizer, which runs an optimization loop:

- Execute the current prompt

- Score the results

- Log results

- Decide whether to stop

- Generate a new prompt if needed

This loop continues until a predefined early stopping condition is met.

Feedback-driven prompt optimization

The most powerful strategy we implemented is feedback-driven prompt optimization, so let’s take a look at it in more detail.

The process looks like this:

- You execute your prompt on training data

- Identify mistakes where an LLM judge was wrong (for classification: where the prediction ≠ target)

- Collect mistake examples with context (input text, target label, incorrect prediction, optional human and LLM reasoning)

- Ask the LLM to improve the prompt based on mistakes

Here’s the actual prompt we use in our prompt optimization strategy:

"I ran LLM for some inputs to do {task} and it made some mistakes.

Here is my original prompt <prompt>\n{prompt}\n</prompt>\n

And here are rows where LLM made mistakes:\n

<rows>\n{rows}\n</rows>.

Please update my prompt to improve LLM quality.

Generalize examples to not overfit on them.

{instructions}

Return new prompt inside <new_prompt> tag"Importantly, with this little comment about overfitting, we explicitly instruct the LLM to generalize, rather than memorize, examples. This prevents it from simply hardcoding example inputs and correct labels (for example, “if the text contains 🚀, output 1”) inside the prompt.

Practical features that matter

Beyond the core optimization strategy, we added several production-focused features designed to make our prompt optimizer reliable and efficient in real-world settings.

Preventing overfitting

To reduce the risk of overfitting, we apply a classic machine learning approach, where the labeled dataset is split into train, validation, and test subsets (by default, 40% train, 40% validation, and 20% test – all configurable).

Prompts are optimized on the training set and evaluated on the validation set. The best-performing prompt is selected based on validation performance, and the final score is reported on a held-out test set.

This ensures that even if a prompt overfits the training examples, it will fail on validation and be discarded – giving much higher confidence in the final optimized prompt.

Early stopping

Early stopping automatically halts the optimization loop when validation performance stops improving. You can configure three parameters:

- Max_iterations: the maximum number of optimization attempts

- Min_score_gain: the minimum required improvement between iterations

- Target_score: a predefined performance threshold (e.g., 97% accuracy)

This prevents wasting compute on diminishing returns and keeps optimization efficient.

Multiple starts (repetitions)

Because LLM outputs are inherently stochastic, different optimization runs can converge to different local optima – even when starting from the same prompt.

Multiple starts allow you to repeat the optimization process several times and then select the best-performing run. This reduces the risk of getting stuck in poor local optima and improves overall robustness.

Performance features

To further streamline optimization, we include several built-in performance features:

- Parallel execution of multiple optimization runs

- Async execution with throttling for efficient LLM API usage

- Caching wherever possible

- A full audit log for transparency and easier debugging

All of these features are available as open source and integrate directly with Evidently’s LLM judge framework, while remaining fully usable as a standalone solution.

Summing up

At Evidently, we built our automated prompt optimization solution around a feedback-based approach. This follows a simple but effective idea: ask the LLM to improve the prompt based on its previous mistakes. This shifts prompt engineering from “carefully rewriting English until it works” to “providing examples of what’s right and wrong – and letting the system learn.”

Since labels or examples of correct outputs are often easier to obtain than perfectly worded instructions, this makes it possible to quick-start the prompt engineering process. The chosen solution performs well even with limited labeled data (often just 5-10 examples are enough).

As a result, Evidently provides a production-ready implementation of automated prompt optimization, including:

- Multiple optimization strategies

- Built-in overfitting prevention (train/validation/test splits)

- Early stopping, multiple starts, and performance optimizations

- Seamless integration with LLM-as-a-judge and other Evidently features

- The flexibility to run standalone or as part of existing Evidently workflows

And yes – it’s open source, so check it out and see how it works!

[fs-toc-omit]Want to try it?

We’ve prepared a case study on optimizing LLM judge for code review classification using prompt scoring and test set analysis. You can follow the step-by-step code example or watch a recording of the live coding session.

[fs-toc-omit]What about generation?

In the example in this blog, we used a classification task and accuracy as an optimization metric. If you want to see prompt optimization for a generation task (where we use an LLM judge to score the quality of generations), you can watch a different video example.

Like the feature? Give us a star on GitHub to support the project.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

-min.png)

.svg)

.svg)